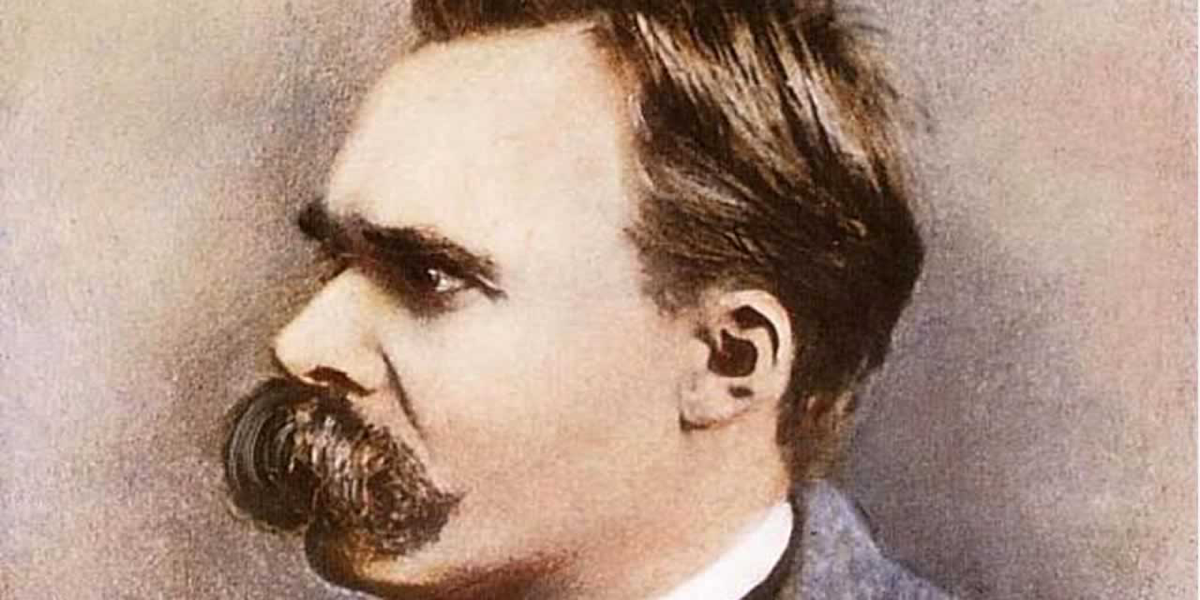

“Thus Spoke Zarathustra” by Friedrich Nietzsche

ietzsche once demurred that Socrates was the “vortex and turning-point [Wendepunkt] of so-called world history” due to the fact that he had renovated Western moral and political thought from the ground up with the dream of an ideal moral and political type. For this reason, Nietzsche was drawn to engage the Socratic project in philosophy:

Socrates, to confess it bluntly, is so close to me that I am almost always waging war with him.

In an unpublished note from the fall of 1883, Nietzsche describes his own thought, particularly the attempted restoration of the pre-Socratic “innocence of becoming” through the teaching of the eternal recurrence in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, in a similar way: “Talk on the innocence of becoming….The teaching [Lehre] of the return is the turning-point [Wendepunkt] of history.” Nietzsche thus claimed that he and his Zarathustra have “split the history of humanity in two parts,” that which came before the novel, following the Socratic innovation, and that which comes after it. Is this boastful claim accurate? Probably not. But let’s consider the novel on its own terms.

In Thus Spoke Zarathustra Nietzsche crafts a most curious protagonist, the eponymous character who teaches three main “doctrines”: 1) the overman (Übermensch), an exemplar for nobility without reference to a metaphysical being. The overman’s creation of values affirms and is made possible by 2) the will to power, a world at variance with itself and the true nature of reality. A recognition of this agonistic nature would seem to liberate the human being for the creation of values that affirm life, were it not for the nagging problem of the passing of time. Historically, the will’s struggle with transitoriness has brought forth a gruesome history of violence and self-denial, which would seem to be unavoidable were it not for 3) Zarathustra’s conceptualization of time as the eternal recurrence of all things. The most enigmatic element of Nietzsche’s novel is the teacher of these doctrines.

So, “Who is Zarathustra?” What is the meaning of his teachings, and how does he stand with the other characters of the novel? In order to answer these questions, I will examine other types portrayed in the novel’s Prologue. Nietzsche found it philosophically useful to mark with broad strokes differences among human “types.” He reflects upon the significance of constructing a human taxonomy in a notebook, kept in preparation for Zarathustra, from the Spring-Summer 1883: “My demand: to bring out the essence, which sublimely represents the whole species ‘human being’ and to sacrifice this goal and ‘the next.’” However, Nietzsche is not attempting to re-establish an ideal “moral type:” “[t]he essential in all endeavors is aimless or indifferent to a possibility of purpose.” Still less should his taxonomy be misconstrued as a form of humanism, such as that forged by Rousseau, Comte, or Mill, which were no more than “hidden forms of the cult of Christian ideals…the cult of Christian morality under a new name.” For Nietzsche, “humanity” per se “does not advance, it does not even exist,” given the shortfalls and successes of such types “scattered throughout the ages.” A philosophical typology of characters is only useful for comparison and critique — as “sacrifices.” In another context, Nietzsche lays out an “order of castes,” in a rather Platonic fashion, “based upon the observation that there are three or four human types” distinguished psychologically (for example the “spiritual type” that “teaches,” which is distinct from the type that fights, or nourishes, or provides services to the other types) which justifies a natural division of labor. But here again, the one moral type is not to be presumed in Nietzsche’s works, because the logic of natural development implies heterogeneity. Even Zarathustra’s characterization of the prototype for human striving and self-overcoming, the Übermensch, should not be interpreted as a singular ideal: “There must be many Übermenschen: all goods develop themselves only amongst their kinds. A God implies a devil! A sovereign race.”

In the opening scenes of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, we are introduced to three ontologically distinct spaces of human existence and four human types: These spaces are 1) the realm of innocence: as Zarathustra is alone with his animals, marking the coming and going of the sun with dawn and twilight. When Zarathustra leaves this realm, he expresses desire to return to human beings, but he must first encounter 2) the realm of the cultural-poetic-narrative. Here, beyond the political hubbub of contractual arrangements and transactions, we find a poetic-narrative that had once organized the lives of all humans, and is still apparently flourishing in the life of the true believer, but is no longer relevant in the marketplace. It seems that the old saint occupying this space had not yet heard in his woods that “God is dead.” We also discover that Zarathustra and the holy man adhere to different poetic-narratives, and in this we deduce that Zarathustra and the people of the marketplace have something in common: they reject the holy man’s no-longer-relevant worldview. Zarathustra’s conversation with the holy man produces the middle term in this ontological triangulation: the political challenge we are about to encounter hinges on the cultural-historical reality of disenchantment: “[b]ut when Zarathustra was alone he spoke to his heart: ‘Could it be possible! This old saint in his woods has not yet heard the news that God is dead!’” We soon discover, however, that Zarathustra and the people of the marketplace observe different poetic-narratives as well. This is revealed when Zarathustra crosses over into 3) the realm of the political, where dissimilarities in narratives are exposed and contested. The functional logic of the triangulation, here, is that any two of the three character types are alike in the respect that they differ from the other — from the third type. Each ontological space, moreover, will define justice in distinct but related ways. This triangular logic will be exploited throughout the novel and is important to remember as we attempt to tease out the essential traits of each character type.

In addition to these spaces, the novel’s opening scenes introduce readers to four character types: 1) the Übermensch, 2) the “last human being” — that is, the person of the marketplace, 3) a priest, and 4) Zarathustra himself. (Other characters will emerge to inform our political reading of the novel.) What then can be said about the four characters drawn in the prologue?

In Ecce Homo we find provisional definitions of three of these four types, the exception being the Übermensch, about whom Nietzsche merely says that misconceptions are common, as it often is mistaken for a half-saint, half-genius, Darwinian monster, or some other form of cult-hero. This description gains clarity by noting that in Zarathustra the Übermensch is juxtaposed with the “last human being,” a creature of the marketplace, who desires only happiness. Again, from the Spring-Summer notebook 1883, we find that for Nietzsche “the last man” has been “generated” historically along with metaphysics. The countervailing “way” Nietzsche wishes to respond to that history would produce “the Übermensch, it is absolutely not [Nietzsche’s] intention to understand the latter as humans of the former sort: rather: the two ways should exist next to one another — possibly separated; the one as the Epicurean gods, in order to be of no concern to the other.” It is the “counter-ideal” to the priestly sort that has empowered moral and political ressentiment and bad conscience. Zarathustra shows us “the übermenschliche [and Dionysian] conception of the world” in that we find “rising up here and there, a completely Epicurean god, the Übermensch, the transfiguration of existence.” That is, Nietzsche is not giving us an “evolutionary” account of a “Darwinian monster,” nor does he intend to convey the triumphal emergence of the Übermensch as the overcoming of and redemption for the failures of the nebbish last human being.

Thus, the two types should not be conceived as belonging together in an evolutionary trajectory but rather they form as countermovements, in the way that a remedy implies an illness and (hopefully) the converse. In a sketch from the winter of 1882–83, we find that “the last man is the opposite of the Übermensch: [they were] created at the same time.” Everything about the Übermensch “exposes the last man as ill and insane.” In a sketch from late-1887 or early-1888, entitled “Der Übermensch, Nietzsche avers that “the European of the nineteenth century” does not represent the progress of the human type, and that a “higher type” of culture is presumed to have emerged “on the most distant place on earth and out of the most distant culture,” in contradistinction to this European. This higher culture now is said to stand with the “whole of humankind…like an Übermensch.”

Nietzsche’s self-appointed task is to facilitate a cultural reorientation in favor of this higher type: “I have internalized the spirit of Europe — now I want to wage the counterattack!” In one of his many sketches drawn in preparation for the novel, he writes that Zarathustra is called into the marketplace at (what Nietzsche believes to be) a watershed historical moment, when the fateful triangulation breaks open in “the most dangerous middle, where it can pass over to the ‘last human being’…characterized through the greatest event: God is dead. Only human beings still have not noticed that they live off of inherited values.” Of those values, those historically embedded expectations for moral, political, aesthetic, and epistemic absolutes — and the type of human being to realize them in the one moral type — are the most troubling “inheritances” from Christianity, passed down from the Socratic “turning point.” Nietzsche’s “fundamental insight,” as it concerns the appearance of the “last human being” in this historical moment — and the inheritance to which he is opposed — is that “‘good’ and ‘evil’ are now seen from the eyes of ‘herd animals.’ Sameness of human beings as the goal.” For this reason, an “evil society” might even be preferred to a petty one. Or, more precisely, the image of the Übermensch stands for “[t]he overcoming of the evil petty inclination…fatherland, race all are relevant here.”

The Übermensch is said to live at a distance from the human being, “like an Epicurean god,” as is also fitting for Zarathustra’s convalescence at the close of Part III. The image represents Zarathustra’s attempt to traverse the ladder of existence, from the political realm into the poetic while peering into and out from the abyss of innocence. A poetic image, the Übermensch is a gift for everyone and no one. Created by Zarathustra in the space of cultural-poetic-narratives, it evidences the realm of innocence, disclosed in the image as a power of transformation — of destruction and creation — within the political. The “[m]ain teaching” here concerns overcoming, transformation: “[i]n our power exists the transformation of suffering to a blessing, of poison to nourishment.” And yet, the Übermensch remains throughout the novel a mere hope, am un-reality: “[t]here are still no Übermenschen. Naked I saw them both, the greatest and the pettiest human beings: and both I found still — all-too-human!” Above all, as a political ideal, as “the perfect type in politics,” as something “übermenschlich, divine, transcendent, it will never be achieved by human beings, sketched at best. … Also, in this narrow form of politics, in the politics of virtue, apparently the ideal of virtue is never to be reached.” Once again, the Übermensch is not to be mistaken for signifying “sameness” or human uniformity: in the Übermensch, Nietzsche and his Zarathustra are affirming “human difference” [Immer ungleicher sollen sich die Menschen warden], according to the dictates of justice: “[h]uman beings are not alike [gleich], so speaks justice [Gerechtigkeit].”

Although we read in Ecce Homo that the ineffectual, last human being will in most accounts seem to be the “good man” of the state, this type is contemptible because it “lives at the expense of truth and at the expense of the future.” In a lengthy sketch critiquing the “good man,” Nietzsche lays out several aspects of its “decadence-instinct,” including: 1) its “lethargy” — in so far as it no longer wants “to alter itself, [is] no longer learning” and presumes itself to be “the ‘beautiful soul;” 2) its “resistance-impotence;” 3) its gullibility to suffering; 4) its need of “the great Narcotica — such as ‘the ideal,’ the ‘great man,’ the ‘hero;’” 5) its “weakness, which declares itself in the fear of emotions…not to be an enemy, not to have to take sides;” 6) its “weakness, which betrays itself in the will-not-to-see anywhere where perhaps resistance would become necessary (“humanity”);” 7) its gullibility to “all great decadents…;” 8) its “intellectual depravity — hate of the truth because it brings with itself ‘no beautiful feelings.’” This so-called good human being also has a “self-preservation instinct” which “sacrifices the future of humanity” in so far as it “fundamentally opposes the political, every broadening of perspectives in general, every seeking, adventuring, being dissatisfied, [and] it denies goals, tasks — they are not even taken into consideration.” In the next entry, Nietzsche adds “bigotry” to this remarkable list of the last man’s faults. The “good human being” is the product of a metaphysical distinction between “good” and “evil” that is presumed to be absolute and to mutually exclude the one from the other. Such a presumption “dreams…that it is getting back to wholeness, to unity, to strength of life.” The “good human being” is the consequence of the long effort to “humanize” the human being in carrying out “the will of God,” but it simply amounts to a “dangerous ideology in psychologics” that produces “the most repellent type, the unfree human being, the bigot [Mucker]; one has taught that only as a bigot is one on the right path to Godhead, only the bigot’s way is God’s way.” For these reasons, the “good human being” is a tyrant: it determines the values that promote “a quite distinct kind of life to exclude all other forms of life…i.e., a certain species of human being treats the conditions of its existence as conditions which ought to be imposed as a law, as ‘truth,’ ‘good,’ ‘perfection’: it tyrannizes.” And yet, this good “is a petty evil; therefore, it is easy for the petty human to be good” in accordance with it.

While the Übermensch is the countermovement to this so-called good man — to the last man — it is within the intellectual purview of the last man that the trap of decisionary politics is created. The “marketplace” represents the conceptual realm of modern politics. The last man has become its subject in a two-fold sense: on the one hand, this being is subjected to the requirements of the marketplace, because it alone is the man who can thrive here. On the other hand, it is therefore the subject who has the privilege of objectifyingnature, history and those humans who are other. With a liberal spirit, it gradually accepts the “arbitrary delimitations of the nation and state,” making its institutions appear more calculative, less just, and “much more cruel and wicked.” As antithetical viewpoints in this space become “hopelessly extreme,” the nation-state threatens to “destroy itself in fever.” When civility loses all currency, a nation-state loses its moorings, and all that remains is the crass — even kitschy — web of power relations: a cruel and wicked society mockingly dismissive of others and absurdly transparent to itself in all its vulgar lack of grace and nobility.

The Übermensch represents the one who would contradict the logic of this space. Outside the marketplace, the Übermensch and the last man stand together as particulars in a sub-contrary relationship: they can coexist as true beings and they cannot both be false. But, inside the marketplace, only the last man can be true. Therefore, as a type, the Übermensch is not only the countermovement to the last man, but it also contradicts the space in which this being alone thrives.

The marketplace is the home of the “good human being,” a collection of “individuals,” where “one soul is in itself just like every soul, or ought to be.” In this space, a completed and total space, beings and their actions are defined without remainder. They are equivocated, as are actions with actions, in order to make humans and their interactions reliable, predictable, certain. Such equivalences are necessary in order to produce the being capable of maximizing exchanges. The marketplace is governed by utilitarian values, emphasizing the happiness of the whole — happiness promotes exchange — thus, “the well-being of the community stands higher than the well-being of the individual” — in so far as “the more several individuals flourish, the greater the collected well-being.” Yet, the logic of utilitarianism permits — indeed, demands — sacrifices of the exceptions to the one moral type. The marketplace’s institutions create moral and political types who can be measured according to the scale of reliable participation. It organizes violence: its laws and processes facilitate inclusions for economic exchange and legitimize exclusions for the collected well-being of the included. “Suspicion is heaped upon exceptions [who] are regarded as guilty.” Here, truth is validated (and people are convinced) with “blood [as] the best of all possible grounds.” It is the site of “pompous jesters [feierlichen Possenreissern]” who are presumed to be “great men” but are only “men of the hour,” esteemed because “the people [das Volk] little understand what is great.” To live here is to live near “the petty [Kleinen] and the pitiful” and to risk being subjected to the “invisible revenge” that reigns in this place. Here, “the middle and the mediocre” are treasured as the highest values. “In the middle, fear comes to an end; here one is not alone; here, there is little space for misunderstanding…here contentedness reigns.” Distrust rules the day: it is the way of “the bourgeoisie, who no longer believe in the higher kind of ruling class (e.g. revolution); the scientific craftsmen, who no longer believe in philosophy; the women, who no longer believe in the higher kind of man.” To live here is to live in an age that “wants first of all, comfort; it wants, in the second place, publicity…; it wants, thirdly, that everyone should fall on his face in the profoundest subjection before the greatest of all lies — it is called ‘sameness [Gleichheit] of humans’ — and honor exclusively those virtues that level and equalize.” It is a age of increasing connectivity via media and opportunities for travel to faraway lands: yet, at this time when “the earth has become small [klein]” the last man hops upon it and “makes everything petty [klein].” The subject of the marketplace is positioned not only against the Übermensch but also in contrast to the holy man who lives beyond the city. Thus, Zarathustra and the holy man (although they adhere to different poetic-narratives) are alike in that their narratives differ from the principles that rule the marketplace.

Although the poetic-narratives of the holy man and the man of the marketplace differ, the types are alike in that they are not governed by Zarathustra’s narrative. In this, both the holy man and the last man are decadents. We find in Ecce Homo that the “priestly” type is decadent because of its hostility towards life, and it is parasitic because it attempts to gain and wield power through a determination of values which is based on the human being’s fears. Although the absolute legitimacy of those values are now denied, “the time is coming when we will have to pay for having been Christians for two thousand years…we rush headlong into the opposite valuations”. In doing so, “one attempts a kind of earthly solution, yet in the same sense — that of the final triumph of truth, love, justice: socialism: ‘sameness of persons’…one likewise attempts to hold onto the moral ideal…” The priest represents the religious tradition of the West and his exile represents that tradition’s standing with the values of the marketplace. The holy man’s God has been replaced by an earthly solution: humanism — “a much too imperfect a thing.” This exchange of values and the embodiment of them, however, does not come cheaply for human beings: “[w]hoever creates the new good as a god has always exchanged the guardians of the old good for a devil.” The conceptual relationship between the last man and the priest is also ruled by suspicion of the higher type: such that the “the petty people…no longer believe in the holy and greatly virtuous (e.g. Christ, Luther, and so forth).” Whereas the market is governed by utilitarian values, “Christianity taught conversely that life should be a test and education of the soul and that there is danger in all well-being. It conceptualizes the value of the wicked.” The marketplace will have none of this testing and training of the soul, nor will it be suspicious of happiness, comfort, the well-being of life in the middle of the herd. But, “beware!” exclaims Zarathustra, “the time of the most contemptible human being is coming.”

Finally, Zarathustra emerges in this light as a political thinker — a “legislator.” In a sketch from early 1884 Nietzsche writes that in the first section of Zarathustra the eponymous character is taken with “desperation and uncertainty” at the earth being ruled by “slaves,” as he addresses kings and philosophers: “who should the earth’s master be? That is the refrain of my practical philosophy.” What is complicated about that? You have made slaves the master. Refrain. ‘The pettiest human’” [der kleinste Mensch]. And, then, in a dialogue sketched in sequence: “‘[w]hat happened was more idiotic than pitiful,’ said Zarathustra to the woman. ‘Fatherland and Folk’ — how the saying mistakenly leads.” Nietzsche, during these same months of preparation for the novel, was thinking about the question of sovereignty, on a grand scale. For example, in a list of “fundamental principles,” again from early 1884, he writes: “[t]he task of global rule [Erdregierung] is coming. And with it the question: how are we willing the future of humanity! New tables of values [are] necessary. And struggle against the representatives of the old ‘eternal’ values as the highest concern!”

In order to understand Zarathustra’s “practical” political thinking, however, we need to better understand Zarathustra as a character type. Much is claimed about Zarathustra in Ecce Homo, but generally as a character Nietzsche has this to say about him: “in order to understand this type, you first need to be clear about what he presupposes physiologically: it is what I call great health.” We must therefore investigate in Zarathustra the “physiological” condition Nietzsche calls “great health.” There is an ambivalence here with respect to health, relative to any particular condition, arising because, on the one hand, this health is not a default condition; it must always be activated. It is “achieved” in body and spirit only through a battle against pathogens, “the stimulants of great health.” On the other hand, there is a risk involved in the acceptance of too strong a virus: “[i]llness is a clumsy experiment on the way to health.” In order for great health to be attained, it is imperative to recognize “how much sickliness can [spirit] take upon itself and overcome — can make healthy.” The means to great health bears a resemblance to the Christian path to salvation, in which the human being becomes better, had it never been sick. A key difference separating the paths is that Christianity harbors a “contempt for, and deliberate desire to disregard the demands of the body” and systematically reduces “all bodily feelings to moral values; illness itself conceived as morally conditioned, perhaps as punishment or as testing.” That is, for Nietzsche, environmental factors condition the body in the production of knowledge and values, which then are reflected back to the body in the form of demands, so that the natural history of the human body and human values have evolved symbiotically. The cultural prevalence of the Christian worldview has left an epigenetic mark on the body, and with it the production of spirit, and these have been passed down through the ages and remain the sites for measuring the state of human health. For the spirit, this means “elasticity, courage, and cheerfulness” must be maintained but also the capacity to take on the illnesses that stimulate the great health. For these reasons, Nietzsche conceives of Zarathustra primarily as a “convalescent.”

The conditions that activate Zarathustra’s convalescence — his capacity for pursuing “the great health” — might include, for example, the metaphysical inheritances of millennia as they are operative in contemporary moral discourses and political institutions. In any event “[t]he energy of health betrays itself in the case of illness in the abrupt resistance against the contagious element.” “What is inherited” over the millennia first given direction by Socrates “is not sickness but sickliness: the lack of strength to resist the danger of infections, etc. the broken resistance; morally speaking, resignation and meekness in the face of the enemy.” A degree of good health is necessary for warding off the most extreme symptoms of this sickliness in order to identify the proper social remedy against decadence and to acquire the will to implement it. Taking these measures may be controversial, because good health is complicated when “all signs of the Übermenschlichen appear as illness or madness in human beings.”

Although Nietzsche proposes to break the history of humanity into two epochs with his Thus Spoke Zarathustra, he also teaches us not to be overly optimistic about the present. His conceptualization of a future democracy filled with “good, trans-Europeans” is not the finale of a universal narrative in history. Indeed, he suspects that modernity might now be approaching a “certain degree of sickness” beyond which convalescence would seem unlikely, if not impossible. Moments of convalescence and remission into pettiness are countermovements. Although one may “experience the profoundest convulsion of heart and of knowledge and emerge…with a sorrowful smile, into freedom and luminous silence,” it will nevertheless be “inevitable” that someone always comes along to find ways of “diminishing” the work of the convalescent. Our pettiness, after all, may seem from time to time to be in remission, but it will always return. In practical politics, pettiness might even be logically inevitable. Although the socialist watchword, for example, “as much state as possible” brings forth the countervailing phrase “as little state as possible,” Nietzsche cautions that it would be presumptuous for individuals to work simply towards the abolition of the state, given our very limited knowledge of what to do without a state, which is due to our ignorance of the historical and psychological reasons for developing and maintaining the state’s metaphysical commitments. Moreover, “Europe’s democratization amounts to the creation of a type prepared for slavery in the subtlest sense,’ which prepares the ground for the development of a countertype who will be “stronger and richer than he has perhaps ever been so far.” Hence, this process amounts to an “involuntary exercise in the breeding of [spiritual] tyrants.” Convalescence negotiates and copes with these tensions. In the context of this form of political coping, it must be regulative and generational — that is, it must direct a course for humanity that spans generations. But, it is also crucial for the liberation and personal well-being of the individual as a modern political agent. Nietzsche calls such work, the virtues sufficient for it, and the accumulated experience of enacting these virtues, “convalescence,” which is achieved by “sounding out” the new “idols” of late modernity’s contemporary political reality.

In Zarathustra we find various political critiques: of the last man, the petty state, the trumperies of the marketplace, the foaming anarchist, and so forth. Convalescence, the political reality of the free spirit, the emergence of the good European, Zarathustra’s “great health,” seeks above all to overcome the petty man’s ignorance and arrogance, and it carries on the work of self-criticism moving towards a new enlightenment by way of pointing towards an innocence — a light-abyss — from which it may be possible to reflect on the pettiness of our times. For Zarathustra, the task of overcoming our petty, metaphysical inheritances is never fully completed. His convalescence stands in the overcoming of metaphysics along with the last man’s reconciliations as a countermovement. Our becoming aware of the differences between reconciliation and convalescence opens up a path for understanding the ways.

Although Nietzsche’s estimation of his project was overly grandiose, it is at least clear that he had attempted to point humans towards a future of increased physiological health and social nobility.

0 comments:

Post a Comment